The cognitive psychologist seeking to improve children’s metacognition

Alicia Forsberg is helping learners understand their memory limitations

Alicia Forsberg studies how working memory and metacognition change across the lifespan. Understanding how these factors relate to long-term learning will help educators and education systems adapt to individual needs, she says. Annie Brookman-Byrne finds out more.

Annie Brookman-Byrne: Why is it important to understand how working memory develops?

Alicia Forsberg: Working memory is the mental sketchpad that we use to hold information in mind while carrying out cognitive tasks. It is limited to about three or four chunks of information at a time, and is especially limited in children. These limitations can constrain long-term learning. I am trying to understand why children’s individual working memory capacities play an important role in learning. Ultimately, I am seeking ways to support learning in children with different working memory capacities.

ABB: What is metamemory, and how does it relate to working memory?

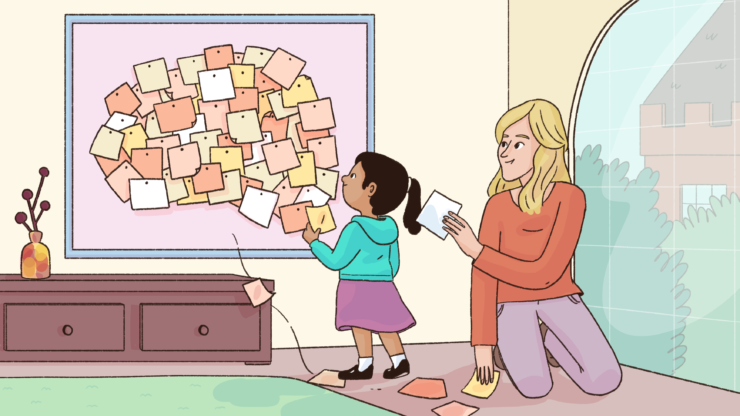

AF: We use our metamemory when we reflect on what we do – and do not – remember. It is a type of metacognition. Metamemory appears to play an important role in how we process information every day, especially when learning new things. If you recognise that you have forgotten a key part of the information you have just learnt, you might go back to review it, or take some other action to reduce the potential negative outcomes of forgetting. I am exploring how metacognition changes during child development, but also in cognitive ageing. My research suggests that children with poorer working memory tend to overestimate how much information they can hold in mind.

“Children with poorer working memory tend to overestimate how much information they can hold in mind.”

ABB: How will your research help learners?

AF: I hope that it will inform metacognitive strategies that teachers, parents, and students themselves can use to support learners’ memory, learning, and cognition. This involves understanding the mechanisms and situations in which learning is most effective, for people of all age groups and with varied working memory and metamemory ability.

Working memory and related metacognitive processes are at the root of all information processing and learning. It is broadly agreed that teaching is most effective when it is adapted to suit the needs of individual learners, and this can mean many different things in practice. In this context, it can be helpful to explore variations in the capacity of working memory and how those limitations influence longer-term learning, and to think of ways to strengthen metacognition.

Unfortunately, some learning environments send the message to certain learners that they are inherently not very good at specific things, leading them to conclude that they are not ‘smart’. As we seek to design a more inclusive and equitable education system, and ultimately society, it is essential to reflect on the ways in which some learning environments are ill-suited to certain students’ needs. I hope that my research will contribute a piece to the puzzle as we move towards this vision, in collaboration with educators, teachers, parents, and others.

ABB: Has working in this field changed how you teach university students?

AF: In my own teaching, I consider how two students who are exposed to the same information may focus on – and remember – very different parts. This is because they have different, and limited, information capacity systems, which are influenced by their prior knowledge; sometimes differences in what they remember is simply random. I experienced this first-hand when I attended my first American football game a few years ago. I didn’t know the rules, the terms, or the players’ names. I struggled to follow what the commentator was saying, especially as I was trying to watch the players at the same time. Owing to my lack of prior knowledge of the game, my working memory capacity was soon overloaded. Hearing others talk about the game afterwards made me realise that I hadn’t even noticed many parts of the game, let alone understood them.

In a similar way, a lack of prior knowledge can limit a learner’s ability to remember and process ongoing events. One student listening to a university lecture may continue to think about a concept that they perceive to be important, making them less receptive to the next concept that is introduced. A different student may judge the first concept to be a less-important anecdote, and therefore be more receptive to the second point. Even very committed students are likely to miss some content completely, through no fault of their own. I therefore allow students to process key information in their own time by providing short, asynchronous video lectures to distinguish essential points from big-picture information that situates the learning in a broader context. This approach is intended to prevent the kind of working memory overload that I experienced at the football match and help students retain key concepts.

“A lack of prior knowledge can limit a learner’s ability to remember and process ongoing events.”

ABB: What are you pursuing next?

AF: I am excited to continue studying the processes that determine what we remember from a given situation – and how these processes may change across the lifespan. This is a challenging area, because many psychological processes are difficult to manipulate, measure, or observe in a straightforward way. But the close link to real-world educational systems makes it very rewarding. Going forward, I am exploring whether basic interventions that improve subjective awareness of memory limitations can help reduce working memory deficits, and whether such interventions can support long-term learning. In addition, I am very fortunate to collaborate with two excellent PhD researchers, Elisabeth Knight and Nada Alshehri, on research projects related to understanding how in-classroom factors like a teacher’s use of gestures, or the presence of an instructor’s face in online lectures, influence learning.

Footnotes

Alicia Forsberg is a Lecturer in Cognitive and Developmental Psychology at the University of Sheffield. She is interested in working memory and the development of memory and attention across the human lifespan, focusing on both child development and cognitive ageing. Recently, she has been exploring the relationship between working and long-term memory as well as the development of object and feature memory. Her research also examines lifespan differences in metacognition and how people approach cognitive tasks. The ultimate aim of her research is to find better ways to support memory and learning throughout the life course. Alicia is a 2023-2025 Jacobs Foundation Research Fellow.

Alicia on X

The Lifespan Working Memory Research Group

This interview has been edited for clarity.

This was a fascinating read. Alicia Forsberg’s work on metacognition is crucial for helping children understand their memory limitations. Thank you for sharing these insights.